Motor function linked to weight, height changes in boys with DMD

Study looked at young patients being treated with corticosteroids

Written by |

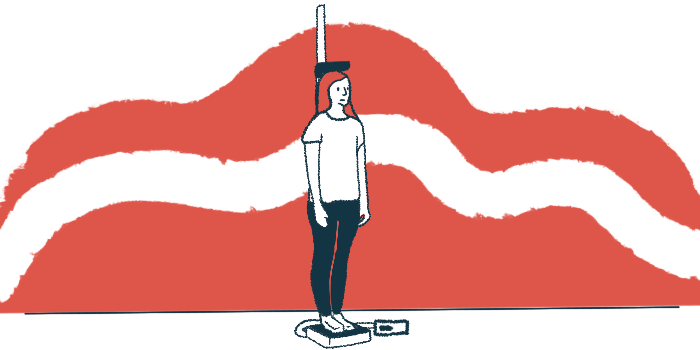

For boys who start corticosteroids to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), being taller is linked to slower growth, while being older is linked to more weight gain as they move into adolescence and near the loss of their ability to walk, according to Phase 3 clinical data.

This implies that doctors should consider a boy’s height before starting corticosteroids. Those who are taller for their age may grow more slowly, likely because they are already closer to the maximum they can grow before puberty starts. For older boys, “weight control is key to preserve function as DMD progresses,” researchers wrote.

These data came from the FOR-DMD Phase 3 clinical trial (NCT01603407), which included boys diagnosed with DMD, ages 4 to 7 years, from five countries. They were randomly assigned to one of three treatment regimens: daily or intermittent prednisone, with 10 days on and 10 days off, or daily Emflaza (deflazacort).

“Treatment should not be delayed due to growth concerns,” researchers wrote in “Height, weight, and body mass index trajectories and their correlation with functional outcome assessments in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy,” which was published in Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology.

Boys taller than average at start of corticosteroid treatment grew more slowly

Like other types of muscular dystrophy, DMD is a genetic disease that causes muscle weakness. Because it is progressive, symptoms tend to worsen over time and may result in loss of motor function. While corticosteroids are part of standard treatment, their chronic use has been linked to delays in growth and short stature.

To understand how growth patterns and weight gain affect motor function after starting treatment with corticosteroids, the researchers drew on the FOR-DMD study. Motor function was assessed based on the time it took to rise from a lying position, the time required to complete a 10-meter (32.8 feet) walk/run, the NorthStar Ambulatory Assessment, and the six-minute walk test.

The data came from 194 boys with DMD from Canada, Germany, Italy, the U.K., and the U.S. who started corticosteroids at an average age of 5.8 years and were followed for three years. Of this group, 32 boys were followed for five years. No participant was being treated with growth hormone.

Boys who were taller than average at the start of treatment with corticosteroids grew more slowly over time, with the growth rate decreasing each month for each unit of height above average. Boys on daily Emflaza grew more slowly, while boys on intermittent prednisone grew faster than those on daily prednisone.

[This study] emphasizes the importance of monitoring weight changes and understanding how baseline traits influence growth and motor function.

At the start of treatment, boys were already heavier than average for their age. Older boys tended to gain weight at a faster rate, similar to the results from body mass index, a measure of body fat that takes into account weight and height. For each additional year of age at the start of treatment, weight increased faster. Boys on daily Emflaza gained weight more slowly than those on daily prednisone, with no difference observed between daily and intermittent prednisone.

Increases in height or weight z-scores, a measure that compares growth to the average for age and sex, were associated with worse performance on motor tests. These associations were weak over the 3-year follow-up period but became stronger at five years, closer to the time when many boys lose the ability to walk.

The findings suggest that growth and weight changes are linked to motor function in boys with DMD. Since weight gain can worsen motor function, careful weight management should be part of treatment discussions, as this may help preserve motor function, the researchers wrote.

While these findings should be confirmed with real-world data, this study “emphasizes the importance of monitoring weight changes and understanding how baseline traits influence growth and motor function,” the researchers wrote.