Family’s Quest for ‘Overlooked’ Duchenne Treatments Leads to Breast Cancer Medicine Tamoxifen

Written by |

Bruce Ward of Royal, Arkansas, and his son, Gavin. (Photo by Larry Luxner)

Gavin Ward, a spunky 8-year-old Arkansas boy with Duchenne, enjoys building contraptions with his Lego set and watching video games. He also walks up to 18,000 steps a day and accompanies his father, Bruce, on outings near their home in Royal, about 70 miles west of Little Rock.

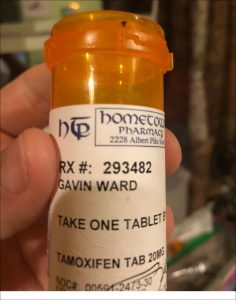

But what makes Gavin stand out in the muscular dystrophy world is this: He’s one of the first in the United States to receive a breast cancer therapy — tamoxifen — to treat his disease.

Tamoxifen, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1998, has since been prescribed to millions of women to both treat and prevent hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer. The once-a-day pill is known, among other things, to reduce the risk of breast cancer coming back by 40 to 50 percent in postmenopausal women, and by 30 to 50 percent in pre-menopausal women. It also cuts the risk of cancer developing in the other breast by about half.

But because it’s a selective estrogen receptor modulator hormonal therapy — meaning that it selectively blocks or boosts estrogen’s action on specific cells — tamoxifen may benefit boys with Duchenne.

David Feder, MD, a Brazilian pharmacology professor who has a son with Duchenne, conducted one of the first studies on the subject in 2004. Earlier this year, scientists at Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte, N.C., published a study showing that the use of tamoxifen and Evista (raloxifene) improved cardiac, respiratory and skeletal muscle functions, and increased bone density in mice with the disease.

Not only is tamoxifen widely available, it’s also cheap. At $20 a month, the generic medication is a fraction of the price of other therapies used to slow the progression of Duchenne, such as Emflaza (deflazacort) — an FDA-approved corticosteroid sold by PTC Therapeutics that can cost anywhere from $35,000 to more than $100,000 per year depending on a patient’s weight.

Bruce Ward claims tamoxifen is far more effective than steroids would have been — and without the harmful side effects. He said that Gavin’s average hand grip strength has increased from 9.5 pounds to more than 14 pounds since October 2017, and that his 6-minute-walk distance has risen from 417 to 445 meters (about 486 yards). The boy began using the medication in late November, six weeks after being diagnosed.

“Gavin has grown two inches and 9 pounds in the same [eight-month] time period,” Ward said. “Growth should theoretically hurt him, because if your bones are longer and you weigh more, it’s harder to move.”

Looking for alternatives to steroids

Ward, a legal researcher by profession, spoke to Muscular Dystrophy News Today in June during the 2018 Annual PPMD Conference in Phoenix. Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, which organized the event, has funded studies into tamoxifen through its Duchenne Registry, but it’s way too early to draw any conclusions on tamoxifen, said PPMD’s founder and president, Pat Furlong.

“He believes in the drug,” Furlong said of Ward. “It’s now in a trial, and we have to wait for the data. In order for something to be clinically adopted, you have to have really good data. So we’re anxious to see the data come out.”

Gavin, who turns 9 in August, received his diagnosis in October 2017. Only five months before, Ward said, his son was walking the hills of San Francisco on a family vacation.

“He was always slower at things like soccer and gymnastics than other boys his age, but not alarmingly so, and we expected him to grow out of it,” Ward said. “He had a growth spurt around his eighth birthday, and at that point it became obvious he was having difficulty climbing stairs. We took him to the doctor for a diagnosis of what we thought was a coordination disorder.”

Gavin’s diagnosis was predicted by a blood test that measures creatine kinase (CK); an unusually high concentration indicates the presence of Duchenne. It was confirmed by genetic testing that identified a deletion of exons 8 to 27 on the DMD gene that produces dystrophin.

“While it was heartbreaking, this was not unexpected,” he said, recalling how he and his wife, Rana, started researching potential treatments and poring online through all the clinical studies on Duchenne conducted the past decade.

Two such trials involving tamoxifen are now underway. The first is an open-label study launched in November 2016 by pediatric neurologist Talya Dor, MD, with Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem. Taking place at that center, it involves fewer than 20 boys and is likely to conclude by year’s end.

The second (NCT03354039), a Phase 3 trial known as TAMDMD, is being led by Dirk Fischer, MD, of Switzerland’s University of Basel. Begun last month and expected to wrap up in June 2020, it’s a randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled 48-week trial involving 99 boys with Duchenne.

“In my analysis, I looked at what was available to us, which often varies based on age,” Ward said. “Gavin is often excluded from clinical trials because he’s older than 7. A lot of these studies are biased toward very young patients. I discovered Dr. Dor’s work with tamoxifen in Israel and was able to learn from parents of her patients about the success they were seeing in treating their children.”

Gavin’s doc: Tamoxifen safe, effective for now

Vikki A. Stefans, MD, is a pediatrician at Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock. She’s also the doctor who prescribed tamoxifen for Gavin after extensive consultation with his parents.

“We prescribe a lot of things that are off-label for children, because no one has tested them for children. But the chances tamoxifen has a lot of side effects for males are not very high. The treatment we would normally use for Duchenne is a steroid medication — and we know there are a lot of side effects with steroids.”

Stefans said she’s not at all opposed to prescribing steroids for patients who can tolerate them.

“I’m old enough to remember what it was like before we had steroids for Duchenne, and the difference is incredible,” she said. “Before steroids, we would watch their breathing function start to decline in the early teen[age] years, and we’d have to time their scoliosis surgery before the breathing got too bad. It was miserable.”

But some boys on steroids become psychotic, and their behavior is “awful,” said Stefans, who follows 40 to 50 patients — nearly all of them Arkansas residents — at her Little Rock clinic.

“Steroids change Duchenne but it’s not a cure. Folks are still very disabled by their late teens and early 20s,” she said. “Tamoxifen is probably similar. I don’t see it as being a long-term cure.”

Even though doctors don’t fully understand the mechanism that helps tamoxifen fight inflammation in muscle cells, Stefans said she felt comfortable enough with the Ward family to go forward with this decidedly unorthodox approach to treating Duchenne.

“Gavin and his dad are very into researching and understanding everything they possibly can about his condition. They weighed for themselves the risks and benefits, and would rather do this than steroids,” she said. “In fact, Gavin is probably my only patient whose dad is actually conducting 6-minute-walk tests on his own. If we don’t get the mileage we hoped for, we can go back to more conventional treatments.”

Added Ward: “Gavin knows he has Duchenne. He has a great understanding of what he’s taking and what it can do for him. We talk as a family about potential medication and what the effects might be, and I let him make the decisions.”

Studies into tamoxifen’s potential

Dor, the Israeli neurologist researching tamoxifen, told Muscular Dystrophy News Today that her study is testing the treatment in patients between the ages of 6 and 16.

“We saw the preclinical results in mice and thought what generic options could be possible for boys with Duchenne. This was our question,” Dor said. “We’re doing this trial without a placebo and we don’t have results yet.”

Patricia Hafner, MD, who’s conducting the Swiss-led study, said five of this study’s 99 patients have been dosed so far. The trial will take place at 11 clinics in the Netherlands, France, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, and the U.K., and is expected to take two years.

“Mice experiments have been really promising, but there’s a lack of data on tamoxifen and boys with DMD,” Hafner said by phone from Basel. “We’re doing this trial to prove whether tamoxifen is safe and if it works to slow down muscular degeneration.”

As part of the trial, Hafner said, “we will be giving two steroids as an add-on, then we have to see whether tamoxifen given with steroids to boys who can still walk is better than just steroids alone.”

In Gavin’s case, he not only can walk, his dad said the boy walks an average two miles a day, and some days as much as four or five miles. (Ward added, though, there has been no requests for push-ups or sit-ups.)

Besides tamoxifen, Gavin also takes Coenzyme Q10 — an anti-oxidant — as well as vitamin D, a multi-vitamin, creatine, Omega 3 fish oil, and sulforaphane (a supplement made from a phytochemical contained in broccoli sprouts).

For now, Ward is banking on tamoxifen rather than any new medical industry breakthroughs.

“I’m very grateful for the work pharmaceutical companies are doing,” he said. “But personally, my focus is on trying to identify treatments that have been overlooked or maybe repurposed to help our son.”