With Zolgensma’s Approval, Scientists Pursue Similar Gene Therapies in Duchenne

Faith Fortenberry, 7; Justin Moy, 18; and Tana Zwart, 34, were honored as “national ambassadors” at the 2019 MDA Conference in Orlando. (Photo by Larry Luxner)

Now that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Zolgensma — the world’s first gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) — experts say a similar gene therapy to cure Duchenne muscular dystrophy isn’t far behind.

On May 24, the FDA gave its long-awaited blessing to Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi), making it by far the most expensive approved drug on earth. AveXis, the Novartis subsidiary that developed Zolgensma, is pricing the one-time intravenous infusion at $2.125 million, payable in installments of $425,000 a year over five years.

“I’ve been in this field for a long time, and the number of new therapies for neuromuscular diseases that are being approved is astonishing,” Grace Pavlath, MD, chief research officer at the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), told Bionews Services, publisher of this website. “I call it the snowball effect. Things are finally coming together.”

The organization’s president and CEO, Lynn O’Connor Vos, hailed Zolgensma in a press release as “another life-altering therapy for the SMA community” and hinted it could “catalyze the development of other gene therapies to treat a range of rare neuromuscular diseases.”

The MDA — the nation’s largest funder of neuromuscular research outside the U.S. government — is an umbrella organization that works with 43 diseases. Last year, it funded 224 grants with a total funding commitment of $58 million.

The Muscular Atrophy News forums are a place to connect with other patients, share tips and talk about the latest research. Check them out today!

Pavlath was interviewed during last month’s 2019 MDA Clinical & Scientific Conference in Orlando, which attracted more than 1,200 delegates. At that event, three patients were honored as “national ambassadors” for the organization: 7-year-old SMA patient Faith Fortenberry, 18-year-old Justin Moy, who has congenital muscular dystrophy; and Tana Swart, 34, who has facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD).

Gene therapy alternatives

Several companies are working on gene therapies for Duchenne, including Solid Biosciences, Sarepta Therapeutics, Audentes Therapeutics, and Pfizer.

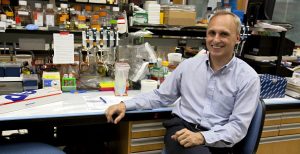

Barry Byrne, MD, is a pediatric cardiologist and director of the University of Florida’s Powell Gene Therapy Center. That facility, located at the UF campus in Gainesville, has done 11 clinical trials with AAV vectors — more than any biotech company.

Byrne is heading a Phase 1/2 trial sponsored by Solid and known as IGNITE DMD (NCT03368742) to evaluate the safety, tolerability and effectiveness of an investigative gene therapy known as SGT-001 in boys between 4 and 17 years old.

“The key issue in patients identified as newborns who are treated with gene therapy is that somatic growth will limit the durability of that treatment,” he said. “Muscle cells are constantly growing, and we increase in size as we get older, so some of the muscle cells will not have been exposed to AAV when it’s delivered early. That leads to a loss of effect. We have an ongoing study where we’re giving multiple exposures of AAV to adults.”

He added: “Even if products were approved today, they’re not being manufactured in sufficient quantities. That has been a big focus of the Solid Biosciences effort.”

Byrne noted that Exondys 51 (eteplirsen) — one of only three FDA-approved treatments for Duchenne — benefits only a small segment of DMD patients and makes very little additional dystrophin, “whereas the systemic administration of AAV leads to the correction of at least 50% or more of peripheral muscle fibers, and almost all of the cardiac muscle cells.”

“So while Exondys 51 doesn’t have any impact on cardiac function, this is a big advance for even non-ambulant patients,” he said. “That’s not often highlighted for the bulk of the existing population who are over 8 years old. The cardiac benefits are going to be substantial.”

Byrne added: “Considering the three sponsors pursuing gene therapies in Duchenne and the pace of enrollment in clinical trials, you can see the huge unmet needs. The patient community is aware of the potential benefits of gene therapy, but there’s limited access because the number of patients not in the study far exceeds the number of available study slots. And that will continue for another three or four years.”

Slashing manufacturing costs

A major consideration for gene therapies — regardless of the disease they are designed to treat — is the high cost of manufacturing AAV.

“Right now, the cost of materials to make the product is probably in excess of $1 million per patient dose. The goal is to make it affordable and broadly available,” Byrne said, adding that at present, the expected multimillion-dollar cost of any gene therapy product would preclude its general availability to those who need it the most.

“But we developed a manufacturing strategy that has a four- to five-fold higher efficiency,” he said, “meaning that if materials to make the product now cost $1 million, we think we can do it for under $200,000.”

Pat Furlong, founder and president of Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy (PPMD), said she hopes a gene therapy to treat Duchenne wins FDA approval in the next several years.

“We are thrilled for the SMA community,” Furlong said. “It is a pivotal time for the development of genetic therapies for rare disorders, and we look forward to the day when Duchenne gene therapy products are approved, accessible and reimbursed for so many who need and deserve these therapies.”

To that end, PPMD recently launched a newborn screening pilot program in New York that will test 100,000 newborns a year, which is roughly half the babies born statewide. Yet it could be years before all 50 states implement newborn screening for Duchenne.

Tim Boyd, director of state policy at the National Organization for Rare Disorders, said such programs are crucial for his nonprofit, which represents more than 270 patient advocacy groups.

“Screening every child born in a state is a huge burden,” Boyd said. “States want to make sure they can implement this in a proper way. All that takes time and money. With newborn screening, we’re seeing that states are doing a much better job than they have in the past, but there’s still a long way to go.”