Protein linked to Impaired Muscle Regeneration in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy

A new study from the University of Liverpool, has identified high amounts of a neutrophil-derived protein in the muscle of a Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) mouse model. The finding shows that the protein hinders stem cells from repairing damaged muscle and it reveals a potential drug target for DMD therapies.

The study, “Elastase levels and activity are increased in dystrophic muscle and impair myoblast cell survival, proliferation and differentiation,” was published in Scientific Reports.

DMD, the most common form of muscular dystrophy, is a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene that lead to muscle weakness and progressive muscle loss. Dystrophin is a key component of a complex that anchors muscle fibers to the extracellular matrix. Lack of dystrophin leads to the loss of the anchorage causing muscle fibers to become sensitive to mechanical stress and damaged during contraction.

In healthy muscle, stem cells activate in response to muscle injury to rapidly proliferate and differentiate into muscle cells in order to repair the damaged tissue. Although the role of the muscle stem cells in the manner of development of DMD is unknown, it is believed that their regenerative capacity is impaired in DMD patients.

University of Liverpool researchers looked at the molecular composition of the extracellular environment that surrounds the muscle cells to understand if alterations in its protein composition could account for the impaired function of muscle stem cells.

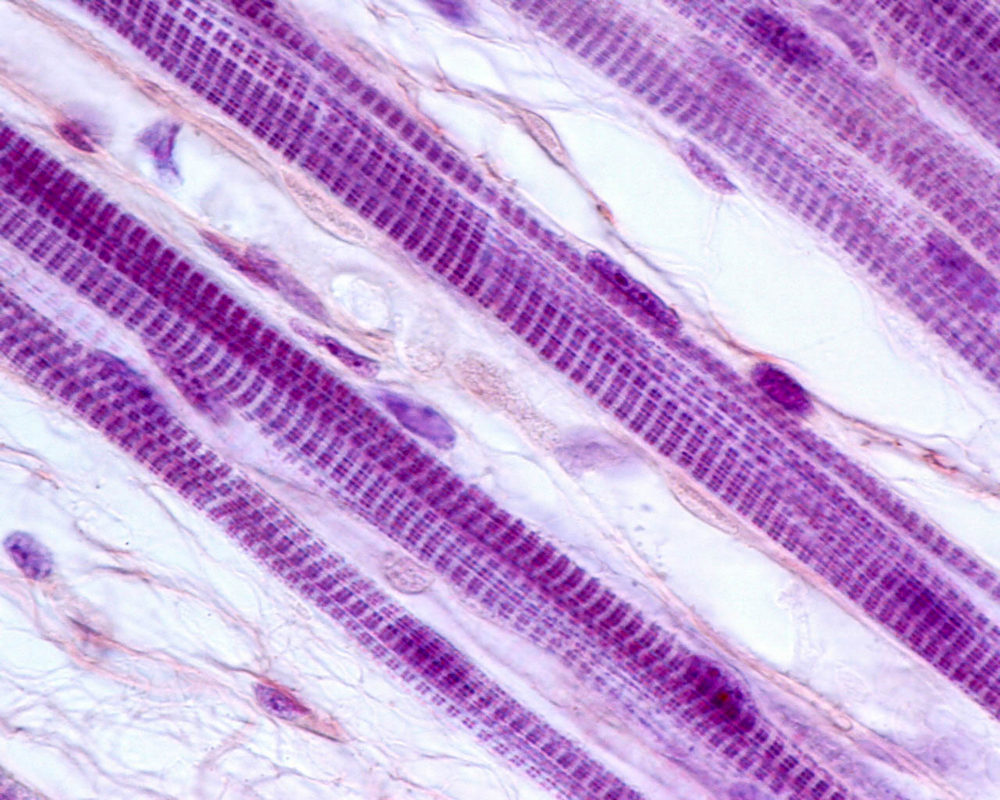

The team collected muscle samples from DMD and normal mice and performed a proteomic analysis that examined protein composition.

The investigators found that dystrophic muscle had high levels of the protein neutrophil elastase, which is produced by a specific type of immune cells called neutrophils that break down several proteins found in the connective tissue to which muscle cells adhere. The increase in elastase levels in the dystrophic muscle was associated with continuous influx of neutrophils to the injured muscle that participated in the establishment of chronic inflammation.

Importantly, elastase activity was found to impair myoblasts’ (muscle progenitor cells) survival, growth, and differentiation in culture. The results prove the importance of neutrophil-mediated inflammation in muscular dystrophy and suggests that elastase production may underlie the loss of regenerative capacity in the dystrophic muscle by impairing myoblasts’ survival and differentiation.

In a press release, Dr. Dada Pisconti, from the University’s Institute of Integrative Biology and senior author of the study, said that while there is not cure for muscular dystrophy yet, newer and better treatments may help control the disease and improve the patient’s quality of life.

“Our next steps are to investigate whether drugs that target elastase are effective and safe as a potential therapy for this disease.” Pisconti said.