CureDuchenne Develops Biobank to Aid Duchenne Lab Research

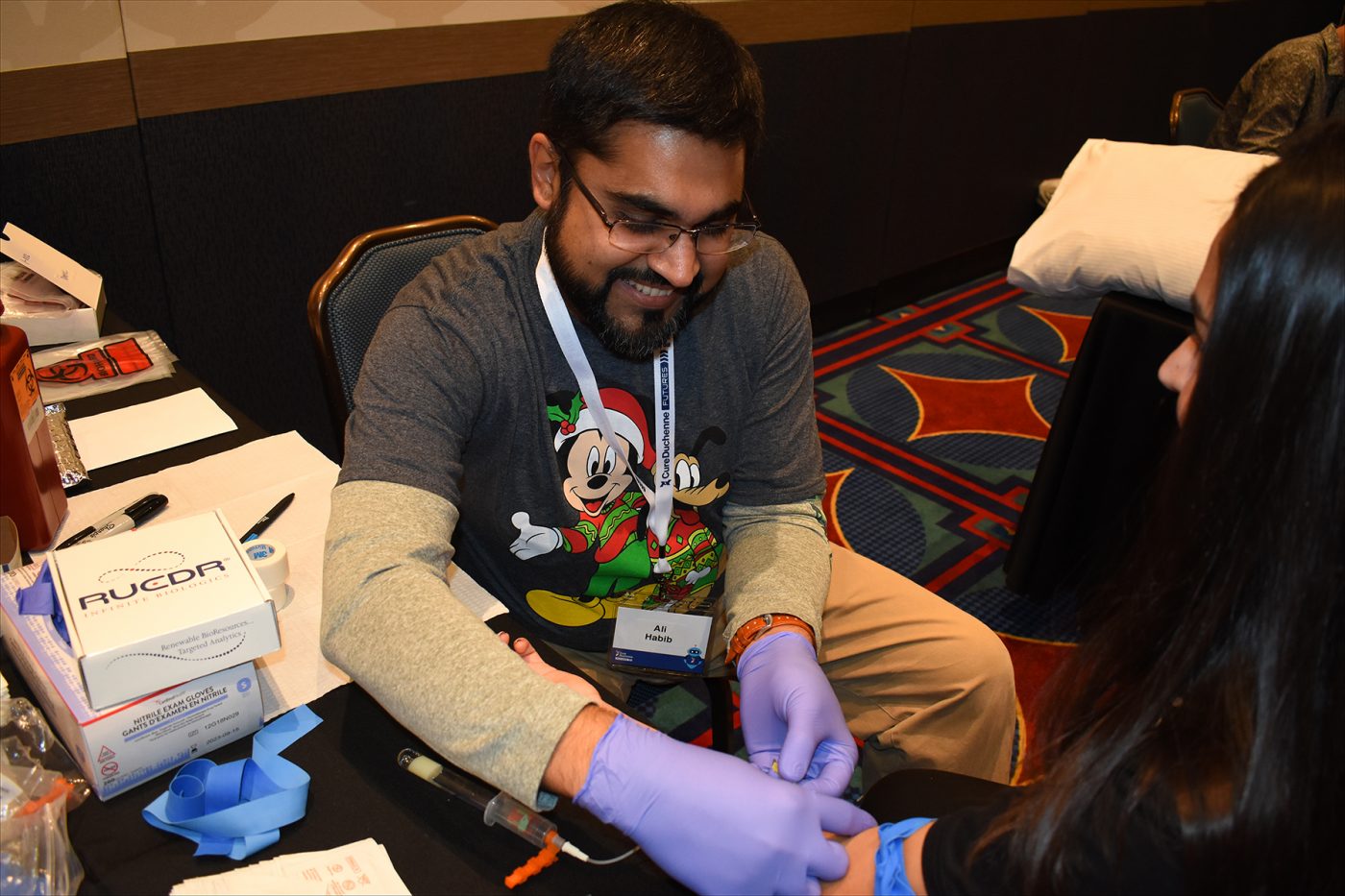

Ali Habib, MD, prepares to collect a sample from a volunteer as part of the CureDuchenne Biobank program, announced during the Futures conference in Anaheim, California. (Photo by Larry Luxner)

CureDuchenne has begun taking blood samples and skin biopsies to facilitate research on new treatments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

The CureDuchenne Biobank is a partnership involving neurologist Tahseen Mozaffar, MD, of the University of California-Irvine and RUCDR Infinite Biologics of Piscataway, New Jersey.

Romina Foster-Bonds, director of programs at Cure Duchenne, said the nonprofit organization took samples from more than 40 people at its 2019 Futures conference, held Oct. 12-13 in suburban Los Angeles.

“More are due to be collected every month through the first quarter of next year. We are encouraged by the numbers with no pre-marketing, and believe we should collect more once we announce our upcoming locations to the community,” she told Muscular Dystrophy News Today.

Added Debra Miller, the charity’s co-founder and CEO: “Nobody’s done this before, at least for Duchenne. There are biobanks in different institutions, but I believe this will be the first Duchenne biobank accessible to all researchers.”

Drawing samples from Duchenne patients, their parents, and unaffected siblings is a relatively painless 10-minute procedure. Skin biopsies will be used to make personalized cell lines, while DNA is extracted from the blood.

By donating specimens to the dedicated CureDuchenne Biobank, families will:

- Enable the development of cell lines specialized to their child’s gene mutation that can be used by any researcher to develop customized treatments.

- Contribute to genetic studies to understand how any mutation in the body affects disease progression and response to therapies.

- Help research investigating how to harness the immune response to allow for more effective treatment.

Miller said the biobank project represents a “significant investment,” though she couldn’t provide a specific dollar figure.

“We’re still building it out, so we don’t know what the cost is going to be. But we are not going to pharmaceutical companies to fund this,” Miller said. “Although we’re seeking the advice of companies and researchers on how to set it up properly and gather the right information, we’ll fund it independently because we want it to be totally accessible to the research community.”

Biobank fulfills a need

CureDuchenne, launched in 2003, has an annual budget of $5 million and employs 15 people. Miller said her organization — which follows the venture philanthropy model — tends to focus heavily on early-stage research.

Mozaffar, a frequent speaker at events sponsored by the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA) and other patient advocacy groups, is director of the UC Irvine-ALS & Neuromuscular Center.

RUCDR Infinite Biologics, a unit of Rutgers University’s Human Genetics Institute of New Jersey, bills itself as the world’s largest university-based biorepository. Since 1999, its scientists have used a technologically advanced infrastructure and high-quality biomaterials to convert precious biosamples into renewable resources, thereby extending research capabilities.

Foster-Bonds said her efforts to establish a Duchenne biobank began when neuromuscular specialists told her of the difficulties they had obtaining samples from such patients.

“Biotech companies asked us if we had access to samples with specific Duchenne mutations. They told us they can’t test what they’re doing unless they had such samples, so there was definitely a gap,” Foster-Bonds said. “And some institutions that do have samples may have limitations on sharing them.”

Foster-Bonds, a molecular biologist, said she reached out to the National Institutes of Health and learned it’s a common problem across the rare disease spectrum.

“They told me that patient foundations are starting to take the lead in creating biobanks,” she said. “They’ve done this in other diseases, and the foundations are taking the responsibility of not just funding them long term but also making sure those samples are accessible to everyone.”