Addressing Metabolic Changes Could Be Effective Treatment in DMD, BMD, Study Suggests

Written by |

Addressing changes in cellular metabolism and oxidative damage may lead to muscle regeneration in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy, a study has found.

The study, “Comparative proteomic analyses of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Becker muscular dystrophy muscles: changes contributing to preserve muscle function in Becker muscular dystrophy patients,” was published in the Journal of Cachexia, Scaropenia and Muscle.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD) are both caused by mutation in the gene that codes for the protein dystrophin. In BMD, this protein is generally present at low levels or functions incorrectly, whereas it is usually entirely absent in those with DMD.

As a result, the clinical presentations of the two disorders differ. Muscle degradation characterizes both dystrophies, but it tends to start earlier and be more severe in DMD than in BMD.

The study suggests that different levels of proteins involved in energy production and cellular support in muscles may help explain the differences between the two disorders.

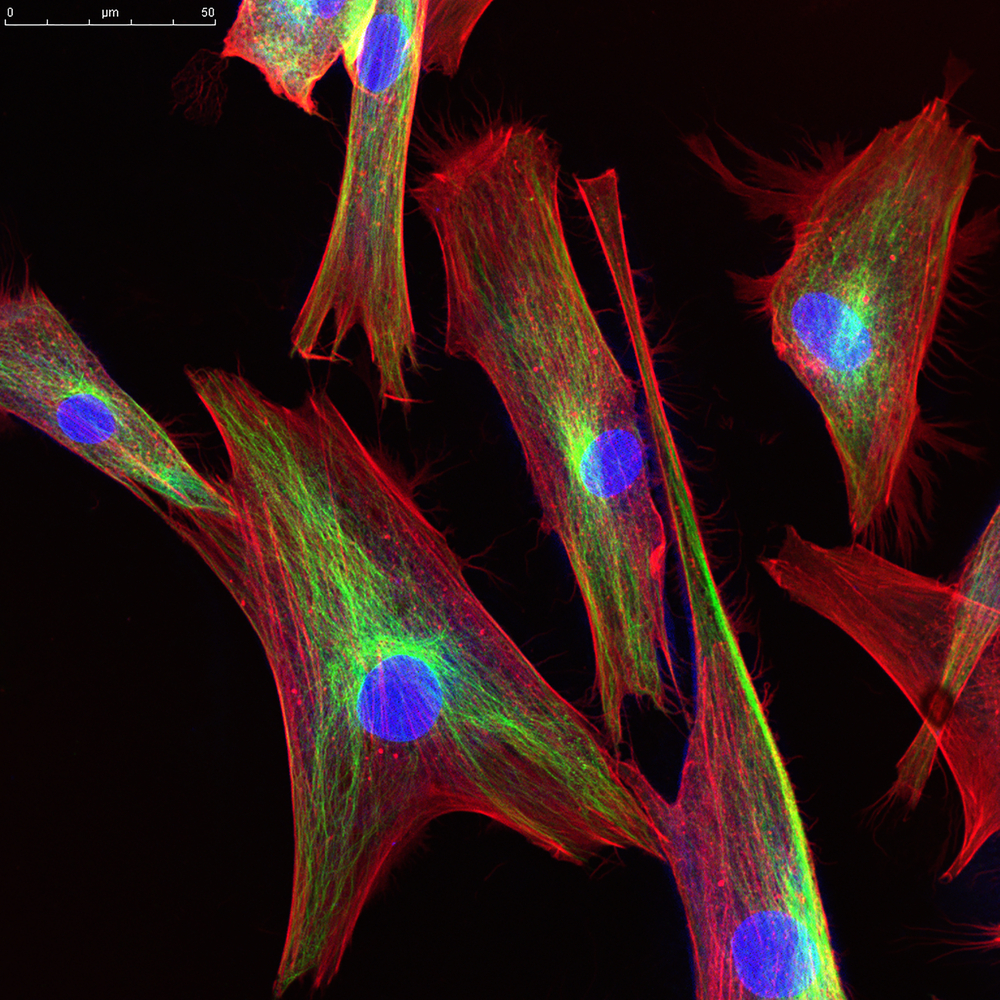

Altered dystrophin activity may partly reveal the difference. The protein interacts with many other components of muscle cells, and its absence or alteration can have wide-reaching consequences in muscle cell biochemistry.

In the study, researchers in Italy and their collaborators performed a proteomics analysis of muscle biopsies taken from 15 people with DMD, 15 with BMD, and 15 healthy controls (all males). Age range in patients was 1–11.

This analysis involves chemistry techniques such as mass spectrometry to simultaneously identify and quantify all proteins in a sample.

In total, the analysis identified 226 proteins that were changed in DMD and/or BMD compared with the controls. In addition, 107 of these proteins were significantly changed between DMD and BMD.

Investigation of these proteins, and their various associated molecular pathways provided some clues as to the consequences of these alterations.

The researchers noted several changes in proteins associated with the extracellular matrix (ECM) — the “scaffold” of proteins and other molecules that provides structural and biochemical support to cells. These changes tended to be more pronounced in DMD than in BMD, and can lead to altered mechanical properties and stiffness of muscle fibers.

Other protein changes in both diseases led to impaired anaerobic metabolism (the cellular production of energy from carbohydrates, or sugar). Samples from DMD patients also showed severely compromised oxidative metabolism, which refers to the use of oxygen to generate energy from carbohydrates. In turn, proteins involved in the breakdown of fatty acids to produce energy were increased in BMD.

Beyond energy, these changes also affected the levels of toxic free radicals called reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage cellular components when they outweigh antioxidant defenses. Broadly, these findings suggested that ROS levels would be lower in BMD muscles than in DMD muscles.

These metabolic and ECM differences likely contribute to the relative resistance to degradation of BMD muscles, compared to those of people with DMD. And they also may open avenues for future treatments, the scientists said.

“Results from the present study provide an overview of the players strictly dependent on dystrophin that contribute to the loss of muscle function,” they wrote.

“[I]t appears that to support muscle regeneration will require intervention at metabolic level decreasing ROS production,” the team added.