Patients with certain mutations lose their walking ability earlier: Study

Genetic testing may help personalize treatment, guide future research: Study

Written by |

Specific genetic mutations in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) influence how long patients retain the ability to walk, even when treated with corticosteroids, according to a study that highlights the importance of genetic testing in predicting disease progression.

These findings are relevant because understanding how fast the disease progresses based on different genetic profiles could help doctors tailor treatment to each patient and guide future basic and clinical research into new medications.

The study, “The impact of genotype on age at loss of ambulation in individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy treated with corticosteroids: A single-center study of 555 patients,” was published in the journal Muscle & Nerve.

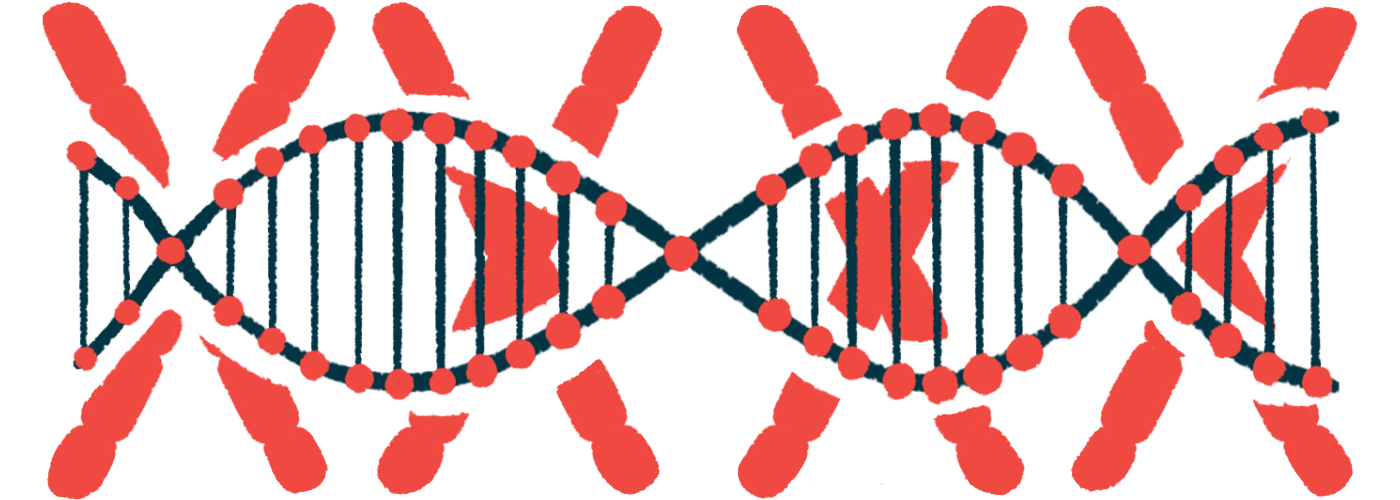

DMD is a genetic disease that results in progressive muscle weakness and wasting. It’s caused by mutations in DMD, the largest known gene in the human genome. This gene codes for dystrophin, a protein that protects heart and skeletal (movement) muscles from wear and tear.

Symptom severity can vary, partly due to patient’s genetic mutations

The severity of its symptoms can vary, partly due to a patient’s genotype, or specific genetic mutations. These variations influence how the disease presents, leading to a milder or more severe phenotype, or the set of observable characteristics in a patient.

Previous studies on genotype-phenotype correlations have included patients both treated and not treated with corticosteroids, a standard treatment used to preserve muscle strength and tissue, which may influence a patient’s clinical picture.

To better understand how genotype correlates with phenotype, a team of researchers reviewed the medical records of a more uniform group of 555 patients who were on long-term treatment with corticosteroids for DMD at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Patients were started on corticosteroids at a mean age of 6.1 years, and they had been receiving either daily doses of the corticosteroid Emflaza (deflazacort) or prednisone, or high doses of prednisone on weekends, for at least 12 months. None of the patients were on other disease-modifying medications.

Nearly two-thirds (63%) of patients had exon deletions, where protein-coding sections are missing from the DMD gene. Fewer patients had exon duplications (15.3%), where protein-coding sections are repeated; and point mutations (12.4%), where a single DNA building block is mutated.

For patient phenotype, the researchers focused on age at loss of ambulation, or the ability to walk, which marks a critical milestone in disease progression. Treatment with corticosteroids lasted from 12 to 168 months (14 years) for those who could walk and up to 297 months (more than 24 years) for those who could not.

Patients with mutations amenable to exon-44 skipping lost walking ability later

Patients with genetic mutations amenable to exon-44 skipping lost ambulation later than those with other genetic mutations. Exon skipping refers to a treatment approach that masks certain exons in the DMD gene to enable the production of a shorter but working version of the dystrophin protein.

In contrast, those with genetic mutations amenable to exon-51 skipping lost ambulation at a younger age. About 3 in 4 patients with deletions of exons 3-7 remained ambulatory past 14 years of age, while a smaller proportion (11.9%) of those with genetic mutations amenable to exon-51 skipping did.

“This study strengthens previously reported knowledge about genotype-phenotype correlations in DMD and highlights key differences between trends in certain genotypes of interest from the rest of the DMD population,” the researchers wrote.

Understanding which genetic profiles respond better to treatment, for example, corticosteroids, can improve personalized care and guide future research into new medications for this type of muscular dystrophy, the scientists added.