Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Trial Design May Mask Treatment Effectiveness

Written by |

A new report titled “Improving clinical trial design for Duchenne muscular dystrophy“, published in the journal BMC Neurology, suggests that some novel treatments for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) may have positive effects in those affected by the disease but these results are not showing up in clinical trials due to the way studies are being designed.

In the report Drs. Luciano Merlini and Patrizia Sabatelli of the Laboratory of Musculoskeletal Cell Biology, Bologna, debated whether specific characteristics of people who participate in clinical trials for DMD could affect measurements of treatment effectiveness.

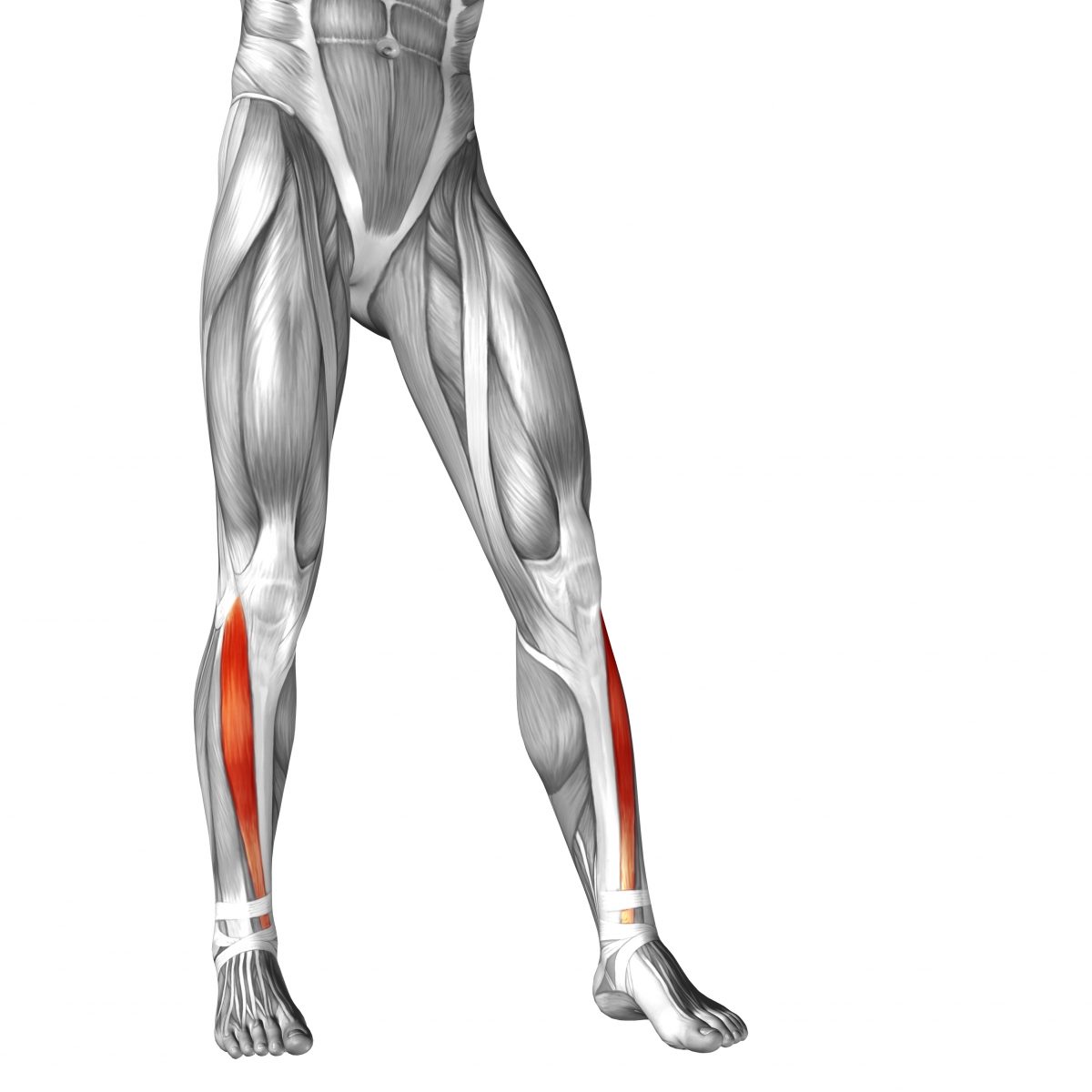

DMD is a genetic condition in which muscles break down and become weak. It is caused by a lack of the protein dystrophin, which is crucial for maintaining healthy muscle cells. Right now, the most promising DMD medications intend to restore lost dystrophin using two genetic strategies known as “exon skipping” and “stop codon read-through.” Unfortunately, in a recent phase 3 clinical trial (the final stage before a drug can be FDA approved) of the exon-skipping drug drisapersen study participants did not appear to improve in the six-minute walk test, the main measurement of drug effectiveness used in this study.

According to Merlini and Sabatelli, several points need to be considered by researchers when designing DMD clinical trials. Specifically, “younger patients have more functional abilities and more muscle fibers to preserve than older patients and therefore are better subjects for trials designed to demonstrate the success of new treatments. Second, the inclusion of patients on corticosteroids both in the treatment and placebo groups is of concern because the positive effect of corticosteroids might mask the effect of the treatment being tested.”

RELATED: Read more recent news about Duchenne muscular dystrophy clinical trials for experimental, new therapies.

Corticosteroids are used to treat inflammation in DMD as well as in many other neurological disorders. Ideally people who are not taking corticosteroids should participate in DMD clinical trials, which could be difficult to achieve based on the common use of corticosteroids in these patients.

The authors also noted that researchers should focus on slowing down DMD rather than improve the disease. Different measurements of DMD slow-down could be used by scientists such as “ability to stand from the floor, climb stairs, and walk, not an increase in muscle strength or function.” They further noted that slowing the disease could take much longer to measure, occurring long after dystrophin levels increase.

Investigators studying treatments for DMD might consider this report and design trials to re-evaluate treatments that have failed in clinical studies. Hopefully these ideas will lead to better treatments for the disease.