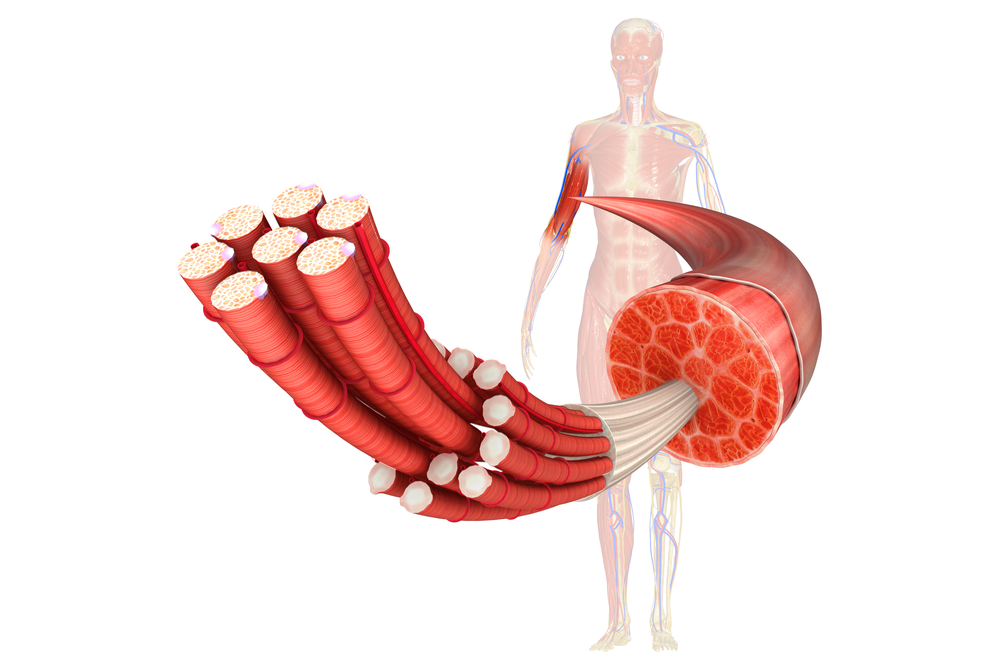

Lab-Developed Contracting Human Muscle Skeletal Tissues Could Impact MD Therapy

Based on the fact that in vitro models of human skeletal muscle cannot recapitulate human muscle functions, a team of researchers from Duke University developed human muscle tissues called “myobundles” using primary myogenic cells. The researchers observed that these muscle tissues were able to respond to electrical stimuli with spasm and tetanic contractions.

In the study led by Nenad Bursac, Associate professor of biomedical engineering at Duke University, and by Lauran Madden, a postdoctoral researcher, these myobundles were efficient in maintaining the function and the structure of “native” human muscle tissues. Furthermore, the researchers tested the response of the muscle tissues using a drug called statins, frequently used to lower cholesterol levels, and a drug called clenbuteral, commonly used to enhance athletes performance. What the researchers observed was that the muscle tissues responded the same way as in humans without causing major adverse effects.

With these results, the researchers indicate that human myobundles can provide a platform for predictive drug and toxicology screening and development of novel therapeutics for disorders affecting the muscles.

[adrotate group=”3″]

“The beauty of this work is that it can serve as a test bed for clinical trials in a dish,” said Nenad Bursac a recent news release. “We are working to test drugs’ efficacy and safety without jeopardizing a patient’s health and also to reproduce the functional and biochemical signals of diseases — especially rare ones and those that make taking muscle biopsies difficult.”

“We have a lot of experience making bioartifical muscles from animal cells in the laboratory, and it still took us a year of adjusting variables like cell and gel density and optimizing the culture matrix and media to make this work with human muscle cells,” said Lauren Madden. “One of our goals is to use this method to provide personalized medicine to patients,” said Bursac. “We can take a biopsy from each patient, grow many new muscles to use as test samples and experiment to see which drugs would work best for each person.”

“There are a some diseases, like Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy for example, that make taking muscle biopsies difficult,” Bursac added. “If we could grow working, testable muscles from induced pluripotent stem cells, we could take one skin or blood sample and never have to bother the patient again.”

The study entitled “Bioengineered human myobundles mimic clinical responses of skeletal muscle to drugs,” was recently published in the online journal eLIFE.